Toyohara Kunichika – my daily art display

When I think about Japanese printmakers I think about the three eighteenth century masters of that genre. There was Hokusai with his well known print The Great Wave off Kanagawa.

Then there was Hiroshige with his many prints, including one of my favourites, Rain Shower at Shōno.

The third of the great eighteenth century printmakers which I call to mind is Kitagawa Utamaro who was one of the most highly regarded designers of ukiyo-e woodblock prints and paintings, and is best known for his bijin ōkubi–e “large-headed pictures of beautiful women” of the 1790s. One of Utamaro’s most famous works being Fukaku Shinobu Koi which set an auction record of €745,000 in 2016. The woman depicted in the title of the print, Fukaku Shinobu Koi means deeply hidden love and the woman has blackened her teeth, a tradition known as ohaguro, the Japanese custom which normally signifies a married woman, but maybe she is not, as her eyebrows are unshaved which would also signify as her being married. It could be that she is still young and only recently married. In her hair she has an ornate kanzashi hairpin with a flower design on it. This type of hairband was often associated with maiko (trainee geisha). The young woman looks down and holds a kiseru tobacco pipe in her right hand. Look at her countenance. She stares off, her shoulders raised, eyes narrowed, and tiny lips pursed, as if in a deep, emotional mid-sigh.

The other day I had the opportunity to see a small exhibition of Japanese prints by Kunichika at the Lady Lever Gallery on Merseyside, He was the most celebrated print designer of the nineteenth century and so I am dedicating this blog to some of his prints as well as looking at the mystical and colourful world of life in Edo and the magic of Kabuki. For the unitiated in Japanese life and culture let me start by talking about Edo, Ukiyo-e and Kabuki.

Kyoto, which had been the historic capital of Japan, was replaced by Edo, a castle town centred around the Edo Castle. Edo became the de facto capital of Japan from 1603 and the seat of the Tokugawa shogunate, the military government of Japan. The period ruled by the Tokugawa shogunate from 1603 to 1868 became known as the Edo period. This Tokugawa military government brought in social segregation by underlining a hierarchal class system which positioned the warriors at the top, followed by farmers, craftsmen, and then merchants at the bottom. The rulers also organised and built walled areas in the cities where theatres, teahouses, and brothels were licensed and which came to be known as the “pleasure districts.” For the Japanese people the Edo period was a relatively peaceful time domestically and the regime’s isolationist policy in relationship to the rest of the world, maintained peace in the country. From this was born an art form that reflected this Japanese lifestyle and which found a new audience amongst a rising Japanese middle class and this art known as Ukiyo-e, was born as an evolution of yamato-e, a previous style of painting. Ukiyo-e depended upon collaboration between four people. The artist, using ink on paper, drew the image that was then carved by a craftsman into a woodblock. A printer then applied pigment to the woodblock, and a publisher oversaw and coordinated the process and marketed the works.

The artist I am featuring today is Kunichika Toyaharo, who was born Yasohachi Oshima on June 30th, 1835 in the Kyobashi district of Edo, which nowadays days is known as Tokyo.

His father, Ōshima Kyujū was the proprietor of a public bathhouse. His father was a poor businessman, and he lost the bathhouse sometime in Yasohachi’s childhood. The boy’s mother, Arakawa Oyae, was the daughter of a teahouse proprietor. At that time, commoners of a certain social standing could ask permission to alter the family name and so to distance themselves from the father’s failure, the family took the mother’s surname, and the boy became Arakawa Yasohachi.

Around the age of twelve, Kunichika became a student of the ukiyo-e master Chikanobu. A year later he entered the studio of Utagawa Kunisada the most popular, prolific and commercially successful designer of ukiyo-e woodblock prints in 19th-century. It was at this point in time that Yasohachi Oshima received his artist name – Kunichika. The name derives from the names of his two masters – Kunisada and Chikanobu.

Kunichika was reputed to be a rather bohemian artist. He married in 1861 and had one child with his wife – a daughter named Hana. Although there is no definitive account of their marriage, it is known that they broke up but it is not known who left whom. What is known is that he was a philanderer and led a nomadic life very rarely staying in one place for any period of time. It is said that he once actually bragged that he had moved one hundred and seven times during his life. His heavy drinking habits and time spent in brothels is well documented by his contemporary artists, Kyosai Kawanabe and Kiyochika Kobayashi and reading between the lines Kunichika was probably an alcoholic with loose morals who could not control his spending habits.

According to Kanichika’s biographer, Amy Reigle Newland in her 1999 book, Time present and time past: Images of a forgotten master: Toyohara Kunichika, 1835–1900, Kunichika got into trouble in 1862 when he made a “parody print” in response to a commission for a print illustrating a fight at a theatre. This angered the students who had been involved in the fracas. They ransacked Kunichika’s house and tried to enter Kunisada’s studio by force. His mentor revoked Kunichika’s right to use the name he had been given but relented later that year. Decades afterwards Kunichika described himself as greatly “humbled” by the experience.

To get an idea of Kunichika’s status in the studio of Kunisada when his mentor died in 1864, of all his apprentices, Kunichika was tasked with producing memorial prints of his late master, one of which was a diptych.

Kunichika embraced modern subjects and his prints reflected the great social and political change which was taking place at the time in Japan. He will be best remembered for his depictions of the Kabuki theatre, and his prints encapsulated the drama and excitement of scenes from popular plays and famous actors. Kabuki, which literally means the art of song and dance, is a world-renowned form of traditional Japanese performance art. It incorporates music, dance, and mime with elaborate costumes and theatre sets. Kabuki dramas depict stories which came from regional myths and history. Kabuki is a bizarre visual display which focuses more on looks than the story itself. The elements which go into the production, such as costumes, lighting, props, and set design compliment aspects of the actual performance such as song and dance. All are presented in grandiose fashion to create a single, spectacular show.

Kunichika produced a set of twenty-four prints featuring each hour of the day. This series is regarded as Kunichika’s finest, completed bijin series. Bijin is a Japanese term which literally means “a beautiful person” and is synonymous with bijyo meaning “beautiful woman”. The prints are a fascinating collection of beauties in different aspects of lives and full of intriguing word-puns and allusions. Th one above is set at 3 o’clock in the morning and we see a mother trying to get her baby to sleep.

The prints are a fascinating collection of beauties in different aspects of lives. At 10 o’clock in the evening we see a courtesan waiting for her client.

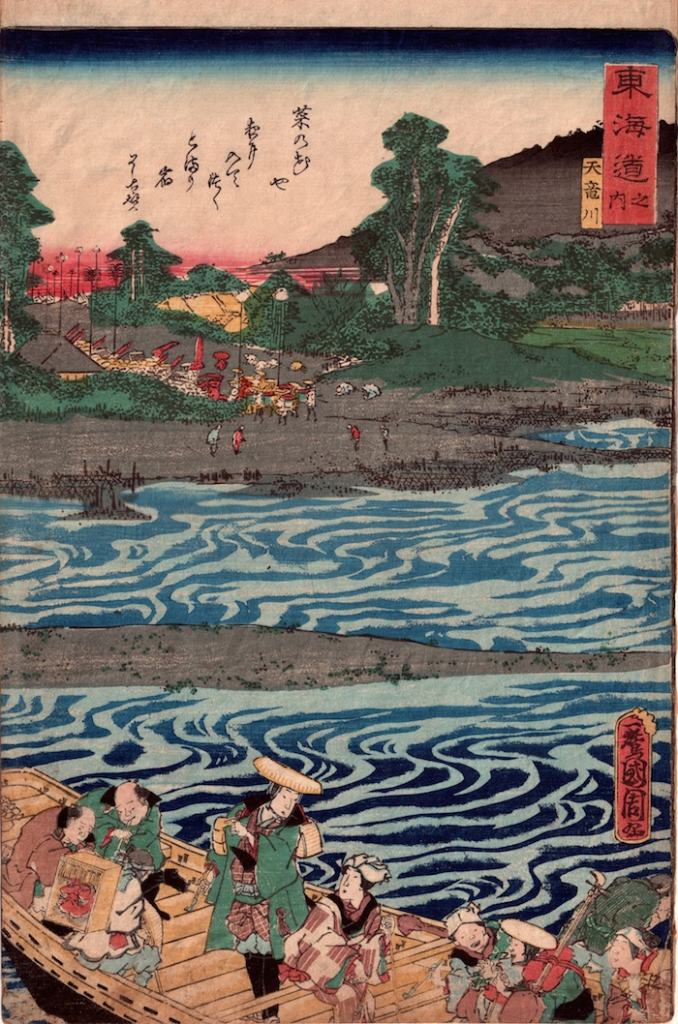

Another interesting set of prints was completed in 1863 and us known as The Tokaido Road Processional series. The print above is one of a series of about one hundred and sixty woodblock prints the authorities commissioned seventeen of the leading ukiyo-e artists of the time The series is a collaborative effort of the various print designers of the Utagawa School in one quite unique effort. What is probably fascinating about the series is despite the differing ages and styles of the artists who contributed to this project, from twenty-four-year-old Tsukioka Yoshitosh to the Master himself, Kumisada, who was seventy-seven, there is a homogeneity about them and it is very difficult to distinguish between them. Kunichika completed seven of this series

Whilst Kunichika was still attending Kunisada’s Kameido studio he was also being influenced by Kunisada’s colleague and rival Kuniyoshi, in the way he has added the swirling motifs of the water taken directly from the Kuniyoshi triptych Xuande Leaping into the Gorge of Tan. In Kunichika’s 1863 print, Scenes of Famous Places Along the Tokaido Road Station 77: Tenryugawa, he depicts figures in a boat in the foreground set against the swirling waves of the seashore.

The background to the depictions is the journey made by Shogun Tokugawa lemchi, Japan’s military leader, who had travelled along the Tokaido Road from the military capital, Edo, (Tokyo) to the Emperor in the imperial capital, Kyoto, for a crisis meeting concerning foreign incursions into their country. The road was an important and busy road used by samurai, officials and merchants during that time. Along the road, there were outposts, inns, temples and shrines at the service of weary travellers. The prints depict the Shogun’s entourage at various beauty spots on the Tokaido Road.

(in the play Matsu no sakae Chiyoda no shintoku)

by Toyohara Kunichika, 1878

Kunichika was a lover of Kabuki theatre and fascinated by the actors. Many of his prints feature the leading actors of the time and snippets of the plays themselves. This woodblock triptych print from 1878 features the three greatest actors of the time, Onoe Kikugorō V playing the role of Kashiwabara Koheita, Ichikawa Danjūrō IX in the role of Tokugawa Ieyasu and Ichikawa Sadanji I in the role of Kakuya Shichirōji in the play Matsu no sakae Chiyoda no shintoku, which was written by Kawatake Mokuami and staged at the Shintomi-za in June 1878. The play, a historical drama, was a portrayal of the life of first Tokugawa shogun, Tokugawa Ieyasu, and was the first commercial production in the Shintomi-za. The play ran for forty-two days, and attracted a total of forty-nine thousand theatre goers.

Many of the kabuki plays were based on historical tales of the past and Kunichika captured one such story in his 1867 woodcut print entitled Ghost of Shinchunagon Taira no Tomomori. The main character was played by the well-known kabuki actor Otani Tomoemon V. He took on the character of the ghost of Taira no Tomomori, who committed suicide after his defeat at the Battle of Dan-no-ura by tying himself to an anchor and jumping into the sea. In the print, he is depicted with the anchor behind him, a rope entwined around it. His face a pale blue to indicate that he is a ghost. His long, wet hair falls over his shoulders, and blood flows from wounds to his head and body. He wears a fine suit of armour with the butterfly crest of the Taira family on the chest plate. A terrific, expressive image with incredible fine detail in the hair.

Another of Kunichika’s prints featuring a “great” of the world of kabuki actors is of the actor Ichikawa Sandanji playing the role of a Suikoden hero. Ichikawa Sadanji I belonged to the triumvirate of stars who dominated the Kabuki world during the Meiji era (1868-1912). The two others “greats” were Ichikawa Danjûrô IX and Onoe Kikugorô V.

My final offering of Kunichika’s woodblock prints is his 1869 work entitled Making A Wish At The Shrine. It is one print from the Tosei Sanju-ni So (Thirty-two Fashionable Physiognomies series), which was one of Kunichika’s major works. The series showcased typical Ukiyo-e beauties but their facial expressions and gestures were livelier and more personalized. These down-to-earth beauties were the harbinger of what became known as Meiji realism which became increasingly popular during the mid – late Meiji period.

Port Sunlight Village, Wirral CH62 5EQ

Kunichika: Japanese Prints

15 April – 4 September

The first exhibition held in a national gallery outside Japan to focus on one of the most important 19th century Japanese print makers.